Not sure which structural system will suit your project? Check out our guide to the pros and cons of the two leading contenders

When it comes to choosing a self build system to suit your project, the views of your architect or house designer and the local availability of trades and materials will all come into play. Two structural options stand head and shoulders above the rest, namely brick and block and timber frame. Here, we’ve set out the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Brick & block

Also known as cavity walling and modern masonry construction, brick and block is the UK’s leading building method. The fact it’s so widely-used can make it a no-nonsense option for your self build, as the system’s familiarity is likely to translate into a cost-effective new home.

How it works

At its simplest, masonry walling comprises an internal leaf of structural blockwork and an external facing of brick. These are separated by a cavity that can be packed with plenty of insulation (usually at least 100mm with a 25mm air gap), while also preventing moisture ingress.

All the work happens on site, with the two masonry leaves built up from the footings in a series of ‘courses’ and fixed together with rust-proof ties, embedded in the mortar lines. Insulation is held in place with special clips attached to the wall ties.

Once the project reaches full storey height, the load bearing internal walls are laid, before the floor structure is fitted and work commences on the walls above. As so much of the work is site-based, you can make changes to the design as the build progresses without adding significant cost.

Bricklaying is a labour intensive wet trade, subject to the whims of British weather. Mortar takes time to cure and can fail if it’s laid in freezing or very wet conditions. You can mitigate the risks by aiming to get the main structure of your home up over the summer months. Another option is to switch from traditional construction to the quick-to-build ‘thin joint system of lightweight blocks, which are laid in 2mm-3mm beds rather than the 10mm required for normal masonry. Thin joint also offers energy efficiency advantages, as the reduced mortar lines help to improve airtightness.

Design options

If you’ve specified good-quality facing units for the exterior of your home, these can stand alone as the finished cladding (a good cost-saving exercise). Options include heritage-inspired handmade or replica brick, or contemporary coloured masonry.

Your choice of ‘bond’ (the laying pattern) will have a big influence on the external aesthetic.

Stretcher bond is the most economical option, while Flemish or English bond offer a traditional decorative touch. If you’re not keen on leaving the masonry bare, opt for a rendered finish or claddings such as glass or timber.

Do bear in mind the structural limitations of a brick and block home. You’ll usually need load bearing internal walls, which means spaces will be broken up into individual rooms. Door and window openings must be supported by sturdy lintels. Judicious use of RSJs will give you the potential for open-plan layouts, as well as eye-catching features, such as glazed external walls.

Energy efficiency

Critics of brick and block often zone in on this area as a weakness, partly because so much not-entirely-ECO concrete goes into the structure. Nevertheless, cavity walling can be used to create cost-effective, low-energy homes – as shown by projects such as the Denby Dale Passivhaus.

The devil is in the detail, both at the design and construction stages. A 125mm cavity stuffed with 100mm of mineral wool may meet the minimum requirements of Building Regulations, but you’ll need more like 250mm to 300mm of insulation to achieve top-end levels of energy efficiency. That translates into a total wall thickness of around 475mm to 525mm.

You’ll also need to combat thermal bridging (where internal heat escapes across ‘bridges’ in the fabric of a building, such as via conductive wall ties or at structural junctions) and improve airtightness (wet plaster provides a better seal than drylining, for instance, but must be completed to a high standard on site – see page 87 for more details).

One of brick and block’s natural advantages over timber frame is its thermal mass. Masonry walls absorb warmth during the day and release it into the house as indoor temperatures drop. This effect can be enhanced via good orientation of the building on its plot and clever use of glazing to maximise solar gain in winter.

Costs & procurement

Most brick and block projects are headed up by the self builder, who in effect becomes the developer and the client. Typically, you’ll work with an architect or house designer to come up with drawings and negotiate with the planners on your behalf for an additional fee.

Once planning permission is in place, these drawings form the basis for putting the project out to tender. Your chosen builder will then act as main contractor, sourcing materials, managing the construction schedule and completing the work. Or you could run the job yourself, commission your architect to do it or hire a professional project manager.

There are a few design and build companies out there who use brick and block, such as CB Homes and Design & Materials. These firms can take the hassle out of a project by undertaking part or all of the scheme on your behalf.

Masonry construction is often the most cost-effective option for building a home. The vast majority of contractor-led projects fall into the £900-£1,200 per m2 category; though you can reduce this if you’re prepared to take on some work yourself. Building the walls themselves accounts for around £80-£ 110 per m2 of that cost (on a standard specification).

Timber frame

This construction method is extremely popular with self builders, who are leading the way in adopting the UK’s fastest growing structural system. At the heart of timber frame’s popularity are its speed and simplicity. Now that costs are broadly in line with brick and block, this building system is a real contender for your project.

How it works

Timber framing has a long history in Britain, taking in everything from early huts to oak-laden Tudor manors. But today the moniker is reserved for modern ‘panellised’ frames, where large-format structural timber sections are factory-manufactured and delivered to site in kit form.

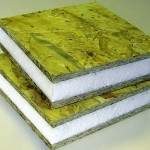

There are two basic types to choose between. Open-panel frames are supplied as studwork sheathed externally. Insulation, windows, etc are fitted on site, before the panel is ‘closed’ internally with plasterboard.

There’s a degree of flexibility during construction as service channels, for example, aren’t necessarily preformed. But the trend in timber framing is towards closed-panel systems, sheathed on both sides, with insulation and service channels already in place. Some suppliers, such as Hanse Haus, deliver the panels to site with windows and doors prefitted. They may even be ready-finished internally and externally.

Either way, the result is an easy- to-assemble home that can be built to an ultra-quick, highly predictable timetable. And the fact it doesn’t rely on wet trades, such as bricklaying, means that construction can continue even in poor weather.

A conventional frame takes about 12 weeks to produce, but you can use this lead time for groundworks and foundations. Once the kit is delivered to site, a professional team can have the shell of your home up within three to five days. So you can reach weather tight stage much faster than with a masonry scheme.

Design options

Timber frame is easily adaptable at the planning stages to suit your requirements; walls can be curved or straight and clad in brick, stone, glass, or quick-fit timber weather boarding and pre-rendered panels.

The load bearing superstructure means internal walls don’t carry the building’s weight, so open plan or partitioned internal layouts are possible. What’s more, interiors are easy to reconfigure at a later date.

However, altering the highly-engineered structural panels once they’ve been manufactured is expensive and time-consuming. So be sure that you’re 100% happy with your design before you sign it off, right down to the location of kitchen and bathroom fixtures.

The accuracy of a panellised timber frame pretty much guarantees straight, square lines. This is a real advantage when it comes to specifying and installing staircases, kitchens and the like, as little or no on-site modification will be needed.

Timber frame does lag a touch behind masonry in soundproofing performance. Measures such as acoustic plasterboard need to be added to panel systems to achieve the same results offered by brick and block construction. But not all projects need this extra treatment – a detached home won’t usually need as much soundproofing as a terraced house, for example.

Energy efficiency

Timber frame performs well in terms of its ECO credentials. Not only is wood a natural and innately insulating product but, provided it’s responsibly sourced, it can be a renewable, carbon-neutral building material.

Green construction also scores brownie points for ensuring low running costs. Building Regulations set a maximum U-value (a measure of heat loss) limit of 0.30 W/m2K for external walls. Most one-off timber frame homes are built with a 140mm insulated frame, which will deliver U-values of 0.24 W/m2K or lower. Finished externally with wood cladding, render or brick slips and internally with plasterboard, walls will be around 230mm to 250mm thick; while for similar U-values, cavity walling needs to be around 300mm.

What’s more, timber frame has the edge over masonry when it comes to airtightness. Its straight lines and millimetre-accurate joins make on-site sealing much easier, so there’s far less opportunity for human error.

Where this system loses out is in terms of thermal mass. With all that lightweight timber, there’s no built-in heat sink to absorb warmth and regulate internal temperatures. Using a concrete ground floor structure or the occasional blockwork internal partition can help to bridge the gap.

Costs & procurement

Many timber frame providers operate as package companies, giving you the opportunity to pick and choose the level of service you require for your home building project. The minimum package is usually the design, supply and erection of the timber frame on site – but many firms are able to take you through the entire process, right up to completion. Combine this with the system’s reliable build schedules and you have a recipe for a home that has every chance of being finished on time and on budget.

Package suppliers typically offer standard house designs that can be tweaked to meet your individual requirements. These tried and tested ‘pattern book’ homes are usually budget-friendly to build.

Yet many suppliers can also cater for bespoke houses, either developed in-house or from your own architect’s drawings. This route will, of course, be more expensive – but provided your plans are informed by economical panel sizes and suchlike, any price hikes are more likely to come from additional design fees and luxury materials rather than increased outlay on the structure.

For several years now, the cost of building with timber frame has been on a fairly even footing with brick and block. That’s because while prefabrication makes for a higher raw materials fee at the structural stages, the ease, accuracy and speed of a panellised build can save you a considerable sum on labour.

In fact, a more pressing concern for your budget is the cashflow requirement for this type of project, since you’ll need to put down a chunky deposit for your frame. So while there’s no issue with obtaining self build mortgage products for timber projects, you do need to ensure that the agreed terms and staged payments are specific to your needs and your project timetable.